3.2 Corruption

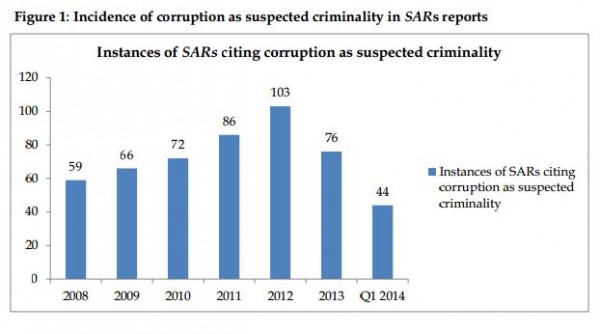

In the past six years there has generally been a steady increase in the number of SARs citing

corruption as the suspected criminality. The first quarter of 2014 suggests that a sharper rise

in this trend is currently taking place. Forty-four SARs cited corruption as the suspected

criminality in this period compared with seventy-six in the whole of 2013. A broader

increase in the incidence of corruption being cited since 2008 is demonstrated in the chart

below.

Figure 1: Incidence of corruption as suspected criminality in SARs reports

3.3 Laundering the proceeds of corruption with PEP involvement

Individuals entrusted with prominent public functions frequently have access to significant

public funds and the knowledge and ability to control budgets, public companies and to

award contracts. They hold a unique position of influence, which may allow them to

circumvent AML/CFT measures by influencing, controlling or evading regulations, or

awarding contracts in return for illicit personal financial reward.

The global reach of Jersey’s financial services industry can pose challenges for relevant

persons in identifying individuals entrusted with prominent public functions, their close

relations and associates (collectively referred to as PEPs).

As well as the difficulty of identification, there is sometimes reluctance on the part of relevant

persons to ask more detailed questions of customers who are PEPs about sources of wealth

and funds. The absence of such information is revealed in some of the cases when further

information is requested by the JFCU in support of SARs that have been filed,

notwithstanding the requirement to apply enhanced CDD to PEPs. It is important for each

relevant person’s Money Laundering Reporting Officer to understand that requesting further

information from a customer as to sources of wealth or funds does not amount to “tipping

off” following the filing of a SAR.

There is an indication that some members of industry appear to view high net worth

individuals with a higher degree of trust and, as such, may ask fewer challenging questions

posed where suspicions of wrongdoing exist. This may be due to commercial pressures.

The JFSC’s on-site examinations have observed this trend; often a relevant person’s risk rating

methodology is found to be too open to subjectivity of the user, which can result in the

failure to apply a high enough score to individual risk factors to raise the overall rating of

the customer, despite there being a clear need to do so.

Notwithstanding the identification of this typology, given the global reach of Jersey’s

financial services industry and client base containing a not insignificant numbers of

PEPs, the vast majority of products and services, and legal persons and legal

arrangements, are used by PEPs for legitimate purposes and current intelligence suggests

only a small minority are used for the purposes of criminal activity.

Corruption typology 1

Company A is a British Virgin Islands’ company specialising in the trading of wines and soft

drinks. The company is settled into a Jersey trust administered by a T&CSP in Jersey. The

managing director of the T&CSP is also its MLCO.

The settlor of the Jersey trust is the executive chairman of Company A. He is a high net

worth individual and prominent businessman domiciled in the Central African Republic.

He is reported to have been a significant financial supporter of the current President’s

election campaign. He has settled a valuable London property into the Jersey trust and also

intends to settle a portfolio of shares in the near future. The Jersey trust is in the top 10 per

cent of fee earners for the T&CSP.

The business relationship was introduced to the T&CSP by a small solicitors’ firm based in

London.

The settlor has been appointed as a special adviser to the African government’s housing

department and is actively engaged in the negotiation of contracts to secure cheap

prefabricated homes for the country’s resident population. In participating in such

negotiations, the settlor has been engaging with companies located in Europe specialising in

providing such homes. The project is being supported and co-funded by the World Bank.

The successful bidder (company based in European Union) pays Company A €1,000,000 as a

consultancy fee. Company A then pays €50,000 to key government figures with

responsibility for approving the housing project contract in the Central African Republic.

The T&CSP files a SAR and seeks the advice of the JFCU. The JFCU issues a “no consent”

letter effectively freezing the funds.

Warning indicators:

- The business relationship was introduced by a small firm of solicitors which may have

limited compliance resources and could have a vested interest in either assisting the

customer (due to other business interests) or putting distance between themselves and

the housing project deal. - By using a British Virgin Islands company settled into a trust, the settlor may be seeking

to disguise his connection to the company. - A small Jersey T&CSP was selected to administer the trust where the managing director

is also the MLCO. Balancing the conflict between the need to secure new customers and

the risk posed by a particular customer may be difficult. A small T&CSP may be more

inclined to accept a high-risk customer in an effort to remain profitable. The customer is

an important fee earner increasing the risk that the relevant person may be less prepared

to challenge the customer on the source of funds. - A developing African state may be more vulnerable to corruption and the settlor’s

political connections make him particularly high risk. - Company A is engaged in buying and selling wines and soft drinks. Receiving €1,000,000

from a company selling prefabricated homes is out of keeping with its business model. - The settlor could be using the Jersey trust as a vehicle to layer the proceeds of corruption

by purchasing a London property and a portfolio of shares. - As the executive chairman of Company A, the settlor is retaining a high degree of

control of business being conducted by the company. - Receiving a large payment from a firm supplying products to a high risk jurisdiction,

followed shortly thereafter by payments to senior government employees engaged in the

negotiation of the original contract suggests that Company A’s accounts may be used as

a money laundering vehicle to launder and distribute the proceeds of corruption. - The cost of the prefabricated home may have been inflated to cover the €1,000,000 bribe.

Corruption typology 2

Mr A is the settlor of a Jersey trust which was established to settle funds that were received

from civil engineering contracts in the US and Africa.

Mr A fails to mention that he held public office in Mozambique and that he was, in his role

as a public official, responsible for awarding construction contracts. As a result of a separate

UK led investigation, a contractor who admitted making corrupt payments identified Mr A

as being responsible for receiving bribery payments.

A review of Mr A’s trust accounts identifies that the contractor paid substantial funds into

Mr A’s Swiss bank account which were then transferred to his bank account in Jersey and

then settled into the trust. Mr A was also unable to provide evidence as to the source of his

funds and also attempted to hide the existence of the trust from his family.

Warning indicators:

- Mr A held public office in a country which was prone to corruption. Notwithstanding

the inadequate CDD held by the T&CSP, which initially failed to positively identify Mr

A as being a PEP, such information that identified Mr A as being a PEP was in the public

domain and, the T&CSP should have been alerted to the fact that Mr A was connected to

a country with corruption problems. - The commercial rationale for the use of a Jersey trust to receive payments in relation to

civil engineering contracts in the US and Africa should have been questioned. - Mr A’s position as a public official, which was a matter of public record, gave him the

power to award construction contracts. It is not simply the fact that Mr A had PEP

status, but more importantly he was in a position that was vulnerable to abuse through

his ability to award contracts. Further, bribes paid to public officials can often be

comparatively small compared to the overall size of the contract and therefore the

amount being laundered can appear immaterial despite the level of the corruption. This

is particularly true of low level corruption. - The use of multiple jurisdictions commingled with personal and corporate bank

accounts used to channel the funds indicates that Mr A may have been attempting to

distance himself from the original source of the tainted funds. - On questioning, Mr A was unable to provide evidence as to the source of funds. Where

customers, who are either prospective or existing, are unable to answer questions and

provide evidence as to source of funds, this should immediately raise concerns and

increase the risk that money laundering might occur.

Corruption typology 3

A government minister, Mr P, from a high risk jurisdiction forms a corrupt business

relationship with the chief executive officer, Mr L, of a government utility supplier. Both

individuals then begin to accept bribes from foreign business suppliers that are contracted to

the utility supplier.

Mr L forms a Jersey registered company (Company R), which is administered by a T&CSP.

Mr L ensures that he has no public association with this company. Payments from foreign

contractors are then paid into the accounts of Company R and then paid into the personal

accounts of Mr P and Mr L in Jersey and other corrupt government figures.

Company R recorded these payments under the guise of “commissions” or “consultancy

fees”. Company R was also unable to provide any proper documentation recording the

source of the payments. Payments from Company R’s accounts were recorded as either

“shareholder dividends” or “interest free loans”.

Mr P and Mr L created a further layer by incorporating a company in a different jurisdiction

which was then used to receive funds originally transferred from Company R. These funds

were then passed on to the final beneficiaries.

Warning indicators:

- The use of corporate structures as opposed to holding accounts in personal names

without a legitimate rationale can be a warning signal that a money launderer wants to

distance himself from the source of the funds. Company R formed a barrier between the

accounts of the foreign contractors and those of the personal accounts of Mr P and Mr L.

This layering technique was further enhanced when the foreign contractors paid

Company R through intermediate companies registered abroad. - A further use of the technique was evident when Mr P and Mr L created an additional

layer by incorporating a company in a different jurisdiction, which was then used to

receive funds from Company R. Relevant persons should ensure that they understand the

rationale behind the use of multiple trusts and companies within a structure. In this case

Mr L created complex layers of financial transactions to separate the illicit proceeds from

their source and in so doing attempted to disguise the audit trail. - As Mr L was the chief executive officer of a government utility supplier he was in a

unique position to influence the awarding of contracts. The receipt of funds from

foreign contractors should elevate the risk of money laundering. A legitimate question

to ask would be why an offshore entity is required and why an entity based in the

customer’s home jurisdiction would not be more appropriate. - Relevant persons should be wary when dealing with structures that involve the receipt of

commissions or consultancy fees. These terms are frequently used as euphemisms for

bribes or other illicit payments. While not all commissions or consultancy fees constitute

illicit payments, relevant persons should have a firm and documented understanding of

the services that have been provided in order to generate such payments. T&CSP that

provide director or other fiduciary services need to be equally mindful of their fiduciary

duties. - In a similar vein, the use of interest free loans which have no security or any realistic

prospect of repayment should also raise the risk of money laundering. This may be used

as a method of facilitating the channelling of funds with little or no prospect of the funds

ever being returned to the company.

Corruption typology 4

The case of AG v Bhojwani highlights various aspects of the corruption typologies

identified above, principally the role played by close business associates of individuals

holding prominent public functions, the use of bearer financial instruments that allow a

degree of anonymity and the inflation of invoiced amounts for goods supplied.

The Defendant was convicted under the Proceeds of Crime (Jersey) Law 1999 of two counts

of converting the proceeds of criminal conduct and of one count of removing the proceeds of

criminal conduct from the jurisdiction of Jersey.

In 1996 and 1997, the Defendant negotiated two contracts with the military dictatorship of

General Abacha, then the President of Nigeria, for the supply of army vehicles to Nigeria at

vastly inflated prices. The illegal surplus of some US$130 million was paid into the

Defendant’s Jersey bank accounts, from where he transferred large sums to accounts in other

countries, including Switzerland, accounts which he knew to be beneficially owned by

Abacha family members and others linked to the regime. The Defendant personally made a

profit of US$40 million out of the two fraudulent contracts, which he held in the name of his

front company at Bank of India (Jersey) between 1997 and 2000.

In October 2000, the Financial Times published a report exposing the late President Abacha’s

corruption in which they revealed that the Swiss authorities had identified accounts

connected with General Abacha into which millions of dollars from Nigerian government

corruption had flowed.

The Defendant, aware that those accounts included sums paid through his company,

immediately converted all the proceeds of the accounts he controlled at Bank of India,

totalling $43.9 million, into freely negotiable drafts. These he then had delivered to London.

The sums remained out of the banking system for 12 days before the Defendant delivered

the drafts back to Jersey to be credited to accounts in the names of different companies

under his control.

After a lengthy trial, the Royal Court found that each of these transactions had been

undertaken for the purposes of avoiding prosecution for an offence in Jersey, or the making

or enforcement of a Jersey confiscation order against him.

The Bhojwani case demonstrated the potential difficulties in prosecuting complex, multi-jurisdictional

offending, and thus the necessity of identifying issues in a timely fashion and

gathering evidence early. Quite often, by the very nature of the offending, those being

prosecuted have considerable resources and influence both in Jersey and beyond, which

they will seek to deploy in trying to avoid the consequences of their crimes. The defendant’s

legal team used an array of applications and challenges throughout the proceedings, from

abuse of process and jurisdictional arguments to judicial review of prosecution decisions.

To help reduce the difficulties in bringing any subsequent prosecution, relevant persons

should be aware of the absolute requirement to make SARs at the earliest possible

opportunity.

The ability to prosecute such a case depended greatly on evidence that could be obtained

from Nigeria, such evidence being relevant to the underlying criminality and the subsequent

laundering of the criminal proceeds. A large degree of cooperation was essential. There is

thus great value in an active and robust SAR regime: the intelligence that SARs provide is

vital in identifying matters that need to be investigated.

Notwithstanding the sums involved, the laundering of proceeds in this case was described

by the Royal Court as “amateurish”. Money laundering can take many different forms and

levels of sophistication. Just as small sums are not necessarily indicative of a less

professional enterprise, so large sums do not always display a high level of professionalism.

The money laundering in this case was undertaken over a short period in an unplanned

reaction to external events.

Warning indicators:

- The use of freely negotiable drafts provides a disconnect between the customer and the

funds. Any instruments that provide such anonymity should be handled with extreme

caution. - Nigeria is a jurisdiction whose public sector is perceived as having a high level of

corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys of corruption

matters. The Defendant’s political connections ought to have easily identified him as a

high risk individual. Extra vigilance should be shown by relevant persons in CDD in cases

of this kind.